“There is now a ‘Mahlerian’ interpretative tradition, but a regrettable number of conductors employ it quite incorrectly. As Mahler once remarked to me, his retouchings were meant for him alone, and he bore full responsibility for them. Today, The Universal-Edition scores of the four Schumann symphonies are sold to the world at large with his amendments incorporated.

“The retouching of Beethoven, Schumann and others was an essential feature of Mahler's interpretation of their works. I cannot go all the way with him on this point. He retouched in the spirit of his age. I believe it was unnecessary, and that one can bring out the full content of such music without retouching. I believe, too, that if we heard a Beethoven sonata played by Franz Liszt today we should be shocked by his arbitrary treatment of it. And yet both things, Mahler's retouching and Liszt's interpretations, were entirely necessary—in their day. Mozart's retouching of Handel's Messiah should similarly be construed in the spirit of the age. He added the new-found clarinet and transcribed the harpsichord part for clarinets and bassoon.

“During the rehearsals for his Eighth Symphony, Mahler quarrelled with the leader of the Munich Philharmonic (I think that was the name of the orchestra) because he wanted an absolutely first-class violinist who was familiar with his style. He sent for Arnold Rosé, who naturally took over the leader's place. At that, the rest of the orchestra rose and quitted the platform with one accord, leaving Mahler and Rosé alone. They did not return until Mahler had agreed that their leader should play in all future rehearsals and performances. This happened in 1910, when we still had monarchies and some respect for authority still remained. What would Mahler say today?”

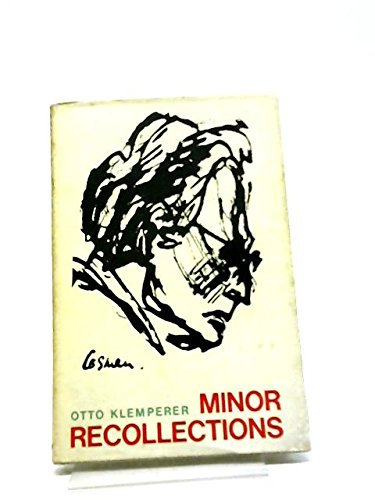

—Page 26-27, Minor Recollections by Otto Klemperer